4036) Did You Know Series (108): A 140,000-Year-Old Sunken World Under the Sea, Filled With Giant Beasts and Extinct Human Species discovered by Archeologists off Indonesia:

Aerial view of Mount Merapi - Mount Merapi rises above the city of Yogyakarta, Indonesia, on the island of Java.

Over the past 2.5 million years, sea levels have waxed and waned around the islands of Southeast Asia, sometimes exposing a sunken landmass and forming a bridge between islands such as Borneo and Java and mainland Asia.

Sundaland's Submergence:

Sundaland was a large landmass that connected Southeast Asia, including Java, Sumatra, and Borneo, during periods of lower sea levels, particularly during the Pleistocene epoch (2.8 million years to 0.012 million years ago).

This landscape, called Sundaland, let animals, including hominins, migrate onto the islands of Southeast Asia.

Now, scientists have discovered some of Sundaland’s former terrestrial residents. In four studies published in May 2025 in Quaternary Environments and Humans, researchers describe the first hominin to be uncovered from this now-sunken landscape, as well as other vertebrate remains.

Beneath the waves off Indonesia, archaeologists have uncovered a shocking discovery that rewrites history. Fossils of ancient creatures and early humans have surfaced, revealing a hidden world that existed long before it vanished underwater.

Underwater Sunken Artificial Reef.

A team of archaeologists has stumbled upon a discovery that will reshape our understanding of early human life in Southeast Asia.

Deep beneath the ocean floor off the coast of Indonesia, a remarkable collection of fossils has been uncovered, dating back more than 140,000 years. This find, confirmed by ScienceDirect, paints a vivid picture of a world that once thrived on what is now the submerged landmass of Sundaland.

The Lost Continent of Sundaland:

The discovery was made in the Madura Strait, between Java and Madura in Indonesia, a region that has long fascinated researchers due to its potential link to the prehistoric continent of Sundaland.

Once a vast landmass connecting much of Southeast Asia, Sundaland was submerged as rising sea levels engulfed the area between 14,000 and 7,000 years ago.

The fossils recovered from the seabed suggest that this landmass was a thriving habitat for both humans and animals during the Pleistocene epoch (2,8 million years to 0.012 million years ago).

Buried under silt for 140,000 years, the skull was only recently confirmed as Homo erectus, reshaping what we know about early human life in Southeast Asia.

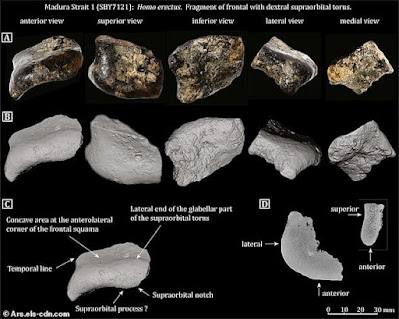

Among the most significant finds were two fragments of skulls identified as belonging to Homo erectus. These remains are believed to be the first hominin fossils discovered underwater in Southeast Asia.

Dated between 162,000 and 119,000 years ago, the fossils were recovered during sand mining operations but were only recently identified by researchers from the University of Leiden in the Netherlands.

A Rich Tapestry of Prehistoric Life:

In addition to the human skull fragments, the site yielded over 6,000 animal fossils, providing a rich tapestry of prehistoric life. Among the remains were Komodo dragons, buffalo, deer, and the now-extinct genus of elephant-like herbivores, Stegodon, which stood over 13 feet tall.

These fossils, preserved in layers of sediment and marine deposits, offer valuable insight into the diverse ecosystems that once flourished in the region.

Alongside the skull, researchers unearthed 6,000 animal fossils from 36 species, including Komodo dragons, buffalo, deer, and elephants.

The discovery suggests that the region, now submerged, was home to a rich and varied mix of species. The remains of large herbivores and predators indicate that the area supported a vibrant ecosystem, much like a savanna, with an abundance of food for both animals and humans.

This once-verdant landscape was, however, doomed as sea levels rose, inundating the plains and creating the underwater world that we are only beginning to understand today.

Evidence of Early Human Adaptation:

One of the most intriguing aspects of the discovery is the evidence of early human activity.

Analysis of the animal remains showed distinct signs of butchery, suggesting that Homo erectus were using tools to hunt and process large animals.

This provides rare evidence of advanced tool use among early humans, supporting the idea that these hominins had developed a level of sophistication in their survival strategies.

The presence of antelope-like species, which typically prefer open grasslands, further supports the idea that the environment was similar to a savanna.

Such ecosystems would have been rich in resources, offering early humans ample opportunities to hunt and gather. This adds another layer to our understanding of how Homo erectus adapted to their environment, showcasing their ability to thrive in diverse and changing landscapes.

As scientists continue to study the fossilised remains and the surrounding geological features, they are uncovering a lost chapter in human evolution that had been buried beneath the ocean for millennia.

The discovery provides valuable insights into the existence and potential migration patterns of Homo erectus when Sundaland was a vast, connected landmass.

This discovery is significant because it provides the first evidence of Homo erectus fossils from submerged Sundaland, suggesting that they lived in a more interconnected and dynamic environment than previously thought.

Implications for Human History:

- The discovery challenges the previous notion that Homo erectus was isolated on Java and highlights their potential for migration and adaptation across Sundaland when it was a connected landmass.

- Prior work in what is now Indonesia suggests the earliest hominins in the area were members of Homo erectus, a bipedal hominin that was the first to harness fire and leave Africa.

- The first of these hominins arrived in the archipelago via Sundaland as early as 1 million years ago.

- The new discoveries required digging in the right place—in staggeringly high volumes.

- In 2014 and 2015, an Indonesian port company dredged about 5 million cubic meters’ worth of sand from the sea floor off Java’s northern coast to build an artificial island.

A small sample of fossils:

A small sample of fossils gathered by geologist Harold Berghuis, including boar teeth, mandibles, and bovid antler, crocodile teeth from two species, elephant teeth and mandible and femur fragments from rhino or hippo.

“We are looking at a very dynamic phase in human history,” Berghuis says. “On mainland Asia we see that the older Homo erectus population is getting replaced by more modern hominins, amongst which were Denisovans and Neanderthals, but on Java—and apparently also on the plains of Sundaland—a relict population of Homo erectus prevailed.”

The haul also reveals how Sundaland’s ancient humans hunted animals.

Some of the bones bear tiny cut and break marks consistent with butchery and the breaking open of bones to collect marrow.

Berghuis even found some bovid mandibles with cut marks on them, which suggests the Sundaland hominins may have had a taste for tongue. “The evidence of butchery marks on some of the faunal remains suggests that Homo erectus selectively hunted fat-rich prime adult prey,” Bello says. “This is the first time that such evidence has been recorded in Southeast Asia, and is suggestive of complex hunting capabilities by Homo erectus.”

The new discovery might also shed light on how early humans in Southeast Asia evolved into dwarf hominins like Homo floresiensis, which lived on the island of Flores likely between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago. “The most logical model is that a group of Homo erectus somehow got on Flores and developed into a small-bodied island population,” Berghuis says.

“One day, in the not-too-distant future, we will have a real understanding of the distribution of hominin populations on the Sunda Shelf.”

Rajan Trikha has commented:

ReplyDelete"Very detailed and informative."

Thank you so much Trikha sahab.

Delete